The rupee as regional currency

Reserve Bank’s move to enable international trade in INR is a step towards regaining Indian primacy in the Indian Ocean region that the Indian Rupee once enjoyed. It is also an essential financial dimension that will add heft to India’s strategic SAGAR policy.

The Reserve Bank of India on Monday, July 11th announced an arrangement that would enable traders to invoice, pay and settle imports/exports in the Indian Rupee [1]. While this move may have been dictated by India’s burgeoning trade with Russia post the Ukraine crisis, it may also be a small step in regaining the central role that the INR used to play in the Indian Ocean region prior to 1947.

One hundred years ago, the Indian rupee was the currency of undivided India under the British Raj, and several other countries either used the Indian rupee or its close derivatives like the Burmese Kyat and the Saudi Riyal, as money. From 1835 to 1939, the Indian rupee was a silver coin of uniform weight (11.66 grams) and purity (91.7%). Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) began using the Indian rupee as currency in 1836. In 1853, Burma brought out a silver Kyat, identical to the Indian rupee in size and weight. From 1881 onward, the Portuguese possessions in India (Goa, Daman and Diu) used the Rupia, which was not only equal to the British Indian rupee in name, size, purity and design but was also minted at the Calcutta Mint. During the 1890s, the colonial empires of Germany, Italy and Britain in Africa – which include present-day Tanzania, Somalia and Kenya – had currencies called the Rupie, Rupia and Rupee respectively (see picture). These coins were also the same as the Indian rupee.

British India One Rupee, Indo-Portuguese Uma Rupia, German East Africa Eine Rupie, Burmese Kyat

British India One Rupee, Indo-Portuguese Uma Rupia, German East Africa Eine Rupie, Burmese Kyat

The use of silver for coinage was dropped during the 1940s in most of the world and in India too, due to the economic pressure of World War II. Newly independent countries went in for their own fiat currencies.

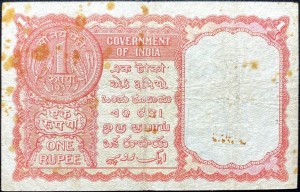

Saudi Arabia adopted a new Riyal in 1935, similar to the INR in weight and silver content, for ease of trade. Its neighbours, the Trucial States (now the United Arab Emirates), Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain and Yemen used the Indian rupee as currency. These countries continued to use the rupee as currency even after 1947: the Reserve Bank of India used to print a special banknote, the Gulf Rupee[2] (see picture), for use in these countries. After the multiple rupee devaluations of the 1960s, these countries dropped the rupee and adopted their own currencies.

Gulf Rupee banknote

India was the region’s largest economy in the 1900s, and it made sense for smaller economies to have a similar currency for ease of trade. As India regains its economic stature a century later, its currency will reflect that. The timing is right. With the increasing weaponisation of the U.S. dollar amidst the Ukraine crisis and political and economic unrest in India’s neighbourhood, countries in India’s sphere of influence can be insulated from such external shocks as are being witnessed in Sri Lanka and Pakistan. There is already significant formal and informal cross-border trade, and the Indian rupee is the defacto hard currency of the region.

This will encourage the desired economic integration of South Asia and the Indian Ocean. It will also make India less vulnerable to sanctions on economic partners such as Russia and Iran.

British India One Rupee, Indo-Portuguese Uma Rupia, German East Africa Eine Rupie, Burmese Kyat

British India One Rupee, Indo-Portuguese Uma Rupia, German East Africa Eine Rupie, Burmese Kyat