Mercantile Bombay: A Journey of Trade, Finance and Enterprise

Mumbai has a deep legacy as an international financial hub from the 19th to early 20th century. It was the central node of trading communities in a globalised colonial world, the remnants of which are seen today. The author describes the city's heyday and advances the prospect of Bombay's revival as a global city of enterprise. This excerpt traces the history of the Bombay Burmah Trading Co., which played a role in the onset of the final Anglo-Burmese War.

By a twist of fate, The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation Ltd. is the holding company of Bombay Dyeing & Manufacturing Co. Ltd. This makes it part of the Wadia group of companies; its chairman Nusli Wadia, is a direct descendant of the famed Wadia ship-builders family, known for their long association with teak timber.

The original trading corporation made its fortune in Burma teak. The company, which today has coffee and tea estates, and other manufacturing interests, was mainly a teak lumbering and trading entity in Burma in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its merchant, William Wallace, was among the first loggers in the then pristine rainforests of Upper Burma (now a part of Myanmar). This Bombay company was also the trigger for the third and final Anglo-Burmese war (1885–1886) against Upper Burma. It was a war that gave Great Britain a monopoly over Burmese resources, particularly its much valued teakwood forests.

The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation Ltd. was originally founded as Frith & Co (Bombay) in 1837, a partnership firm between a Bombay-based merchant Framji Nusservanji Patel and a Scotsman from Edinburg, J.G. Frith. The partnership firm largely dealt in Manchester piece goods (cloth); it was also an agent for the British Government of Ceylon for sourcing a variety of goods from the subcontinent and England. It changed its name to Wallace & Co. when the Scottish Wallace family became a partner.

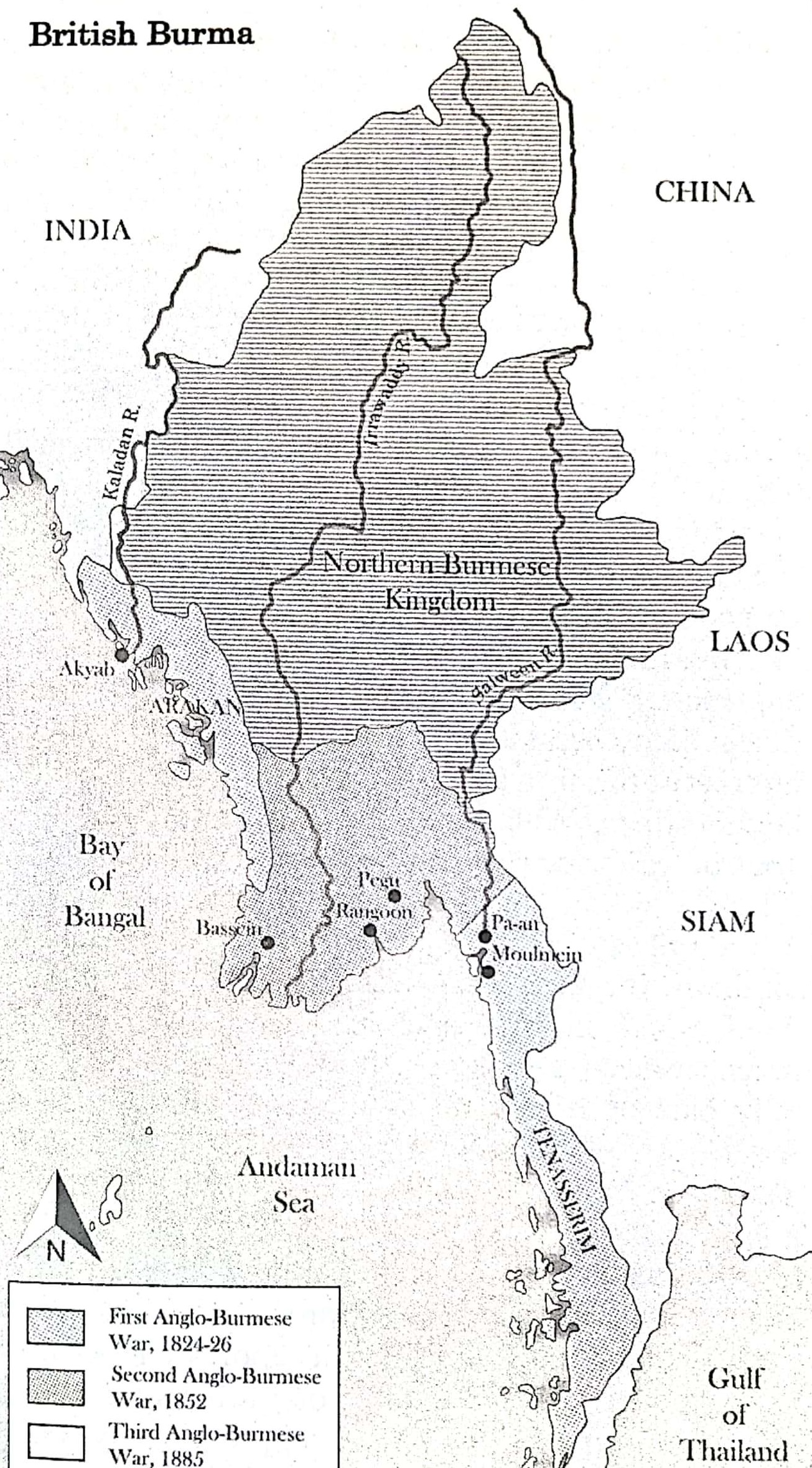

The trading interests of this firm changed drastically when the oldest of the six Wallace brothers, William, visited Burma to oversee the supply of 1,500 tons of teakwood that had been contracted from a firm from Moulmein, Lower Burma. This supply was destined for Bombay and for work on the railways in India. William witnessed in the (by then British) southern Burmese provinces of Arakan, Pegu and Tenasserim in 1855, which had harbours on the rivers Irrawaddy, Sittang and Salween, respectively, a brisk trade in teak. These territories were already part of British ruled southern Burma after the conclusion of the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826) and the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo (24 February 1826) between the Burmese and English.

An indication of the scale of business in teak, which was by then needed to build the railways in India, provide for the shipyards, as well as supply exports to England and China, was a report of 1886 by Sir Dietrich Brandis, the first British conservator of Burma’s forests. He states that between the years 1857 and 1864, approximately 85,000 tons of teakwood was exported every year. And from 1883 to 1884, the annual average export was 275,000 tons (Pointon 1963). As the Lower Burma forests slowly depleted because of excessive logging by various companies that bought teak concessions (permissions), logging companies began looking north to the Upper Burmese kingdom. One of the earliest to make an inroad in acquiring logging concessions from King Mindon, and later from his son King Theebaw, was William Wallace.

These concessions were viewed as risky in Bombay by the partners of Wallace & Company. The Upper Burmese kingdom was totalitarian (which meant that contracts could be rescinded on a whim), and the still simmering friction with British-ruled southern Burma made large investments in North Burmese teak concessions financially risky. To minimise this risk, the partnership firm of Wallace & Co. floated a new company – The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation – this way, it could monetise William’s investments in Burma. This company was incorporated on 4 September 1863, and William Wallace’s risky Burma ventures were acquired by it in 1864. The time coincided with the share market boom of 1863–1865 in Bombay, which was fuelled by money pouring into the city due to the demand for Indian cotton. The American Civil War (1861–1865) had led to an embargo on exports of American cotton from the southern American states, which starved England’s textile mills of raw cotton. Bombay’s hinterland of present-day south Gujarat and former Maratha territories (by then under Bombay Presidency), including the cotton growing tracts of present-day Karnataka, made the city the transhipment port for the export of the coarser short staple Deccan cotton to England.

But in just 20 years after its incorporation, the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation found itself mired in an international ‘incident’ at the Tinsel Court of King Theebaw at Mandalay (Upper Burma). It was fined Rs. 22 lakhs by the Hutlaw (Imperial Council), which believed the company had logged more than it had paid for. This contentious claim between the Hutlaw and a British Indian company came at an opportune time. Sir Winston Churchill, in his biography of Sir Randolph Churchill, his father and secretary of state for India (June 1885-January 1886), referred to the Hutlaw’s contentious claim as the ‘lucky incident’ that gave Great Britain the excuse to invade Upper Burma in the Third and final Anglo-Burmese War (1885–1886) (Pointon 1963). Incidentally, King Theebaw, Queen Supalayat and their family were exiled in Ratnagiri, a coastal district south of Bombay islands, then part of its Presidency. In a moving tribute to the exiled Burmese royal family in her book The King In Exile: The Fall Of The Royal Family Of Burma, author Sudha Shah describes how the exiled King Theebaw spent his last days observing through his telescope ships moving past the coast of Ratnagiri, evidently to and from Bombay. Little did the exiled King realise that the port city of Bombay was by then the axis for security, commerce and culture in the western Indian Ocean, and the reason for his downfall.

Burma teak was an important part of the valuable Bombay–China trade, whose better-known goods were cotton and Malwa opium. It was the China trade – often used as a euphemism for the highly lucrative but illegal (in China) opium trade – that not only brought great wealth to Bombay and its merchants but also ruined many a Bombay family fortune in the aftermath of the First Opium War (1839–1842)